Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Alcohol And The Literature of the American South

The Adventures of Huckleberry Gin by Mark Twain

A Street Bar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams

The Kahlúa Purple by Alice Walker

Gone with the Wine by Margaret Mitchell

Port and South by John Jakes

The Wine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood by Rebecca Wells

The Liver Rants by James Dickey

Beerfest at Tiffany's by Truman Capote

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Friday, November 25, 2011

Thursday, November 24, 2011

Certified Sif: New Video From Sif Ous

If you're thinking of fucking with them, best not.

"There's low-budget, there's no-budget, and then there's my son and his friends." - Point Five's Mom

"There's low-budget, there's no-budget, and then there's my son and his friends." - Point Five's Mom

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Animal Romantic Comedies

The 40-Year-Old Sturgeon

Dove Actually

You've Got Tail

You've Got Quail

You've Got Whale

You've Got Snail

Boar Weddings and a Funeral

There's Something about Mare

Along Came Pony

My Big Fat Beak Wedding

My Big Fat Geese Wedding

50 First Drakes

Foals Rush In

While You Were Sheeping

Sheepless in Seattle

When Hare Met Sally

Sex and the Kitty

Sex and the Kitty 2

How to Lose a Fly in 10 Days

As Good As It Goats

Ass Good As It Gets

My Best Friend's Shedding

Notting Eel

10 Things I Hate About Ewe

Moose Congeniality

Pretty Wombat

Scent of the Wombat

My Bear Lady

Sweet Home Alligator

Mammal Mia!

Dove Actually

You've Got Tail

You've Got Quail

You've Got Whale

You've Got Snail

Boar Weddings and a Funeral

There's Something about Mare

Along Came Pony

My Big Fat Beak Wedding

My Big Fat Geese Wedding

50 First Drakes

Foals Rush In

While You Were Sheeping

Sheepless in Seattle

When Hare Met Sally

Sex and the Kitty

Sex and the Kitty 2

How to Lose a Fly in 10 Days

As Good As It Goats

Ass Good As It Gets

My Best Friend's Shedding

Notting Eel

10 Things I Hate About Ewe

Moose Congeniality

Pretty Wombat

Scent of the Wombat

My Bear Lady

Sweet Home Alligator

Mammal Mia!

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Sunday, November 20, 2011

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Review of The Edge of Things, in Wordsetc

An edge is the most exhilarating point for a story to place itself.

Ask any reader. We don’t need cliff-scrabbling above a literal

precipice; masters (and mistresses) of the form can hollow out spaces of

mystery and risk beneath the most prosaic inner or outer landscape. But

what we do ask, as readers, is that the threshold matter somehow and

that we are surprised and, perhaps, even changed when the story crosses

it.

The Edge of Things, then, is an enticing title and a flexible one too, stretching to cover all manner of brinks. Characters cross the endlessly fascinating boundary between innocence and experience, naivety and self-knowledge, one sharing his first kiss at the company picnic, another beheading her first chicken.

What would infidelity look like? one story wonders, while another shows us what looks like cheating but turns out, in the flick of a needle, to be bridal branding instead. Worlds collide: matter-of-fact house renovations clang against soul-exchanges in one story while in another an empty house invites a range of intruders, from teenage lovers to lowering-the-tone buyers to symbolic creatures, recalling District 9, that challenge notions of inside and out.

Liesl Jobson’s “tips for super pics” apply with wit and pain to parent-child relationships, tracing shifts that the photographer protagonist catches out of the corner of her eye while her lens is trained elsewhere. Beatrice Lamwaka writes about a schoolgirl who wants to win a race on sports day. She has, after all, trained hard, fleeing rebel soldiers who abducted her. “I outran them so that’s an A+ for me. If anyone needs more practice in athletics, I’m sure it’s not me.”

Sometimes, an edge is sharp enough to draw blood. Then there’s literary edginess, fun with texts, intertextuality. Iconoclasm (“I don’t like Coetzee”) meets homage, for example, in Jeanne Hromnik’s exploration of new-South-African father figures both lecherous and pathetic. Perd Booysen amuses himself, and us too, with the device of the discovered journal, inadmissible as historical evidence because of its fictional finesse.

In David wa Maahlamela’s playful bus ride across the fiction/non-fiction frontier, we meet both Wordsetc and its editor, Phakama Mbonambi. In the optimistic view of the narrator, also called David, writers who describe lived experience “know exactly the impression they are intending to give their readers”. But this is perilous terrain for less adept scribes.

An event that bit your heart for real needs just as much construction on the page as a situation you make up from scratch. You can’t refer to that day, you must weave it, as Bernard Levinson does in “Tokai”. We have no idea whether the story draws on his life or his imagination or some alchemical meld of the two. What matters is that he shapes place, time and action so fully, so deftly that, like the narrator, we are moved by the mysterious intensity of the last scene.

The Edge of Things is in every sense a mixed bag. Alongside Levinson’s story, gems include Salafranca’s unforgettable image of a mother in an iron lung and Pravasan Pillay’s characters, dialogue and spicy small-canvas family drama.

Silke Heiss’s “Don’t Take Me for Free”, arguably Best in Show, nimbly outstrips our expectations. Like its trucker-clown narrator, Vonny, the story “was built to change”.

In Vonny’s extended appeal to her lover, “All-I-Have, Azar”, the language is as elating as the ride across ostrich and canola country in a bright-eyed van “with its massive, roaring heart and load continuing to doer ’n gone”.

The collection’s subtitle – South African short fiction – proposes that we read the stories as a kind of national sampler. (In a one-off slip, the introduction makes an unwarranted claim to be presenting writing “on our continent”.) Clearly, South African fiction has moved beyond the imperative to be earnest, political or even particularly South African. Mischief is now acceptable story territory, while Fred de Vries’s chilling tale could take place in almost any big city and Aryan Kaganof’s junkies claim that Amsterdam may as well be Durban, “there’s no fucking difference. Bars are the same everywhere. Drugs are the same everywhere.” But it is also true that, as per Hromnik, “the past is hungry”.

Several stories tackle a mix of race and privilege, either head-on or obliquely. In “Telephoning the Enemy”, for instance, Hans Pienaar crosses the “what if ?” line for an intriguing revisit of apartheid-era violence.

Solitude, as Salafranca notes in the introduction, features in many of the stories. We glimpse various anxious, closed, self-referential worlds. A man sits at a café table in the last story, telling himself consoling untruths and inking “NARCISSIST” into his crossword puzzle as he fends off contact.

What feels like a limitation, though, looking back over the collection, is neither inner landscapes nor low spirits (excellent fiction fodder) but rather a sense of stasis in some of the stories, a single note struck and held, Act 1 from curtain up to curtain down.

For these writers and for all the rest of us, Jenna Mervis’s story offers advice. Her protagonist “mentions nothing of … the fingernails of trees that have begun to tear at her corrugated roof in the night”. She looks for “a sign that … that the dangers outside have become manifest”. But by the end (and this won’t spoil it for you), she steps off the edge of the deck and plunges into the veld. Why not, writers? Instead of tamping down tension, why not let it explode? Approach the edge. Plunge. Leap.

REVIEWER: A Zimbabwean filmmaker and writer, Annie Holmes has published short stories in the US and Zimbabwe and a short memoir, Good Red, in Canada. She co-edited, with Peter Orner, Hope Deferred: Narratives of Zimbabwean Lives.

(Published in Wordsetc, Third Quarter 2011)

The Edge of Things, then, is an enticing title and a flexible one too, stretching to cover all manner of brinks. Characters cross the endlessly fascinating boundary between innocence and experience, naivety and self-knowledge, one sharing his first kiss at the company picnic, another beheading her first chicken.

What would infidelity look like? one story wonders, while another shows us what looks like cheating but turns out, in the flick of a needle, to be bridal branding instead. Worlds collide: matter-of-fact house renovations clang against soul-exchanges in one story while in another an empty house invites a range of intruders, from teenage lovers to lowering-the-tone buyers to symbolic creatures, recalling District 9, that challenge notions of inside and out.

Liesl Jobson’s “tips for super pics” apply with wit and pain to parent-child relationships, tracing shifts that the photographer protagonist catches out of the corner of her eye while her lens is trained elsewhere. Beatrice Lamwaka writes about a schoolgirl who wants to win a race on sports day. She has, after all, trained hard, fleeing rebel soldiers who abducted her. “I outran them so that’s an A+ for me. If anyone needs more practice in athletics, I’m sure it’s not me.”

Sometimes, an edge is sharp enough to draw blood. Then there’s literary edginess, fun with texts, intertextuality. Iconoclasm (“I don’t like Coetzee”) meets homage, for example, in Jeanne Hromnik’s exploration of new-South-African father figures both lecherous and pathetic. Perd Booysen amuses himself, and us too, with the device of the discovered journal, inadmissible as historical evidence because of its fictional finesse.

In David wa Maahlamela’s playful bus ride across the fiction/non-fiction frontier, we meet both Wordsetc and its editor, Phakama Mbonambi. In the optimistic view of the narrator, also called David, writers who describe lived experience “know exactly the impression they are intending to give their readers”. But this is perilous terrain for less adept scribes.

An event that bit your heart for real needs just as much construction on the page as a situation you make up from scratch. You can’t refer to that day, you must weave it, as Bernard Levinson does in “Tokai”. We have no idea whether the story draws on his life or his imagination or some alchemical meld of the two. What matters is that he shapes place, time and action so fully, so deftly that, like the narrator, we are moved by the mysterious intensity of the last scene.

The Edge of Things is in every sense a mixed bag. Alongside Levinson’s story, gems include Salafranca’s unforgettable image of a mother in an iron lung and Pravasan Pillay’s characters, dialogue and spicy small-canvas family drama.

Silke Heiss’s “Don’t Take Me for Free”, arguably Best in Show, nimbly outstrips our expectations. Like its trucker-clown narrator, Vonny, the story “was built to change”.

In Vonny’s extended appeal to her lover, “All-I-Have, Azar”, the language is as elating as the ride across ostrich and canola country in a bright-eyed van “with its massive, roaring heart and load continuing to doer ’n gone”.

The collection’s subtitle – South African short fiction – proposes that we read the stories as a kind of national sampler. (In a one-off slip, the introduction makes an unwarranted claim to be presenting writing “on our continent”.) Clearly, South African fiction has moved beyond the imperative to be earnest, political or even particularly South African. Mischief is now acceptable story territory, while Fred de Vries’s chilling tale could take place in almost any big city and Aryan Kaganof’s junkies claim that Amsterdam may as well be Durban, “there’s no fucking difference. Bars are the same everywhere. Drugs are the same everywhere.” But it is also true that, as per Hromnik, “the past is hungry”.

Several stories tackle a mix of race and privilege, either head-on or obliquely. In “Telephoning the Enemy”, for instance, Hans Pienaar crosses the “what if ?” line for an intriguing revisit of apartheid-era violence.

Solitude, as Salafranca notes in the introduction, features in many of the stories. We glimpse various anxious, closed, self-referential worlds. A man sits at a café table in the last story, telling himself consoling untruths and inking “NARCISSIST” into his crossword puzzle as he fends off contact.

What feels like a limitation, though, looking back over the collection, is neither inner landscapes nor low spirits (excellent fiction fodder) but rather a sense of stasis in some of the stories, a single note struck and held, Act 1 from curtain up to curtain down.

For these writers and for all the rest of us, Jenna Mervis’s story offers advice. Her protagonist “mentions nothing of … the fingernails of trees that have begun to tear at her corrugated roof in the night”. She looks for “a sign that … that the dangers outside have become manifest”. But by the end (and this won’t spoil it for you), she steps off the edge of the deck and plunges into the veld. Why not, writers? Instead of tamping down tension, why not let it explode? Approach the edge. Plunge. Leap.

REVIEWER: A Zimbabwean filmmaker and writer, Annie Holmes has published short stories in the US and Zimbabwe and a short memoir, Good Red, in Canada. She co-edited, with Peter Orner, Hope Deferred: Narratives of Zimbabwean Lives.

(Published in Wordsetc, Third Quarter 2011)

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Victoria Williams: 0129

He’s the second most important – wait, let me rephrase that – one of the most important...

Sunday, November 13, 2011

Friday, November 11, 2011

Thursday, November 10, 2011

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Sunday, November 6, 2011

Friday, November 4, 2011

Thursday, November 3, 2011

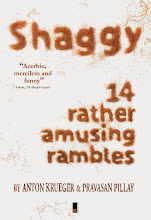

Acerbic, merciless and funny

Playwright, poet and dramaturge Dr Anton Krueger has been exceedingly prolific of late.

The Rhodes Drama lecturer has written three books recently: Experiments in Freedom- issues of identity in new South African Drama, for which he was awarded the Vice-Chancellor’s Book Award 2011; a poetry anthology called Everyday Anomalies; and Shaggy, a collection of ramblings/monologues he co-wrote with Pravasan Pillay.

The latter was launched at NELM’s Eastern Star Gallery recently, producing chuckles and a fair amount of squirming as Krueger’s deliberately banal brand of humour was shared with the gathering.

Prominent local poet, Harry Owen, who introduced the book, revealed how it was written in a remarkable way after Pillay and Krueger struck up an online friendship a few years ago. Finding that their shared a subversive brand of black humour, they decided to co-write what they call “fourteen stories written by creeps, losers and an idiot”.

The two have only met face to face on a few occasions yet their writing seamlessly melds into a distinctive and indistinguishable style. As Owen noted, one doesn’t know who wrote what. One of these ramblings, 'The Actress', came about when Krueger sent Pillay an article about a vacuous actress expressing her regret that her twin babies couldn’t share in her elation for an award she has yet to receive. Pillay is currently based in Sweden.

Shaggy was launched in Pretoria and Cape Town earlier this year, where some of the pieces were performed by professional actors. Owen describes the effect of reading it as “hilarious but uncomfortable; you squirm in your seat, asking yourself, could I be that one?”

Deliciously subversive and filled with bathos, almost everyone and everything is raked over the coals; from self-important academics to delusional community leaders; parodying the many idiocies of South African life. “He puts a pin into pomposity, ego and ignorance... deflates self-delusions, but does it lightly, with a smile” says Owen. He likened the seemingly pointless humour to Monty Python, Alan Bennet (Adding: “now that’s a compliment!”) and Ken Kesey’s One flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest .“Biting, cutting commentary, acerbic, merciless but above all, funny,” he concluded.

Krueger then read 'The Activist'. It is told from the rather warped perspective of the ‘leader’ of the Margate University Communist Society, who chastises fellow members for not forgoing their cell phones and continually updating their Facebook statuses.

It soon becomes a jumbled ride into the mind of a down-and-out, power hungry, washed-out student, who puts his foot into it by inadvertently revealing his own admiration for high status jobs and fat salaries, coupled with an (un)healthy penchant for Grand Theft Auto. Packed with gems such as: “Suggestions for lectures entitled ‘Revolutionising 24-hour clock time’ and ‘Why poor people have less money,’” Krueger had the audience guffawing with laughter, concluding the banal and absurd diatribe with the immensely ironic “...now that’s enough laissez-faire discussion for one meeting!”

by Anna-Karien Otto

20 September 2011

First published on the Rhodes University website.

The Rhodes Drama lecturer has written three books recently: Experiments in Freedom- issues of identity in new South African Drama, for which he was awarded the Vice-Chancellor’s Book Award 2011; a poetry anthology called Everyday Anomalies; and Shaggy, a collection of ramblings/monologues he co-wrote with Pravasan Pillay.

The latter was launched at NELM’s Eastern Star Gallery recently, producing chuckles and a fair amount of squirming as Krueger’s deliberately banal brand of humour was shared with the gathering.

Prominent local poet, Harry Owen, who introduced the book, revealed how it was written in a remarkable way after Pillay and Krueger struck up an online friendship a few years ago. Finding that their shared a subversive brand of black humour, they decided to co-write what they call “fourteen stories written by creeps, losers and an idiot”.

The two have only met face to face on a few occasions yet their writing seamlessly melds into a distinctive and indistinguishable style. As Owen noted, one doesn’t know who wrote what. One of these ramblings, 'The Actress', came about when Krueger sent Pillay an article about a vacuous actress expressing her regret that her twin babies couldn’t share in her elation for an award she has yet to receive. Pillay is currently based in Sweden.

Shaggy was launched in Pretoria and Cape Town earlier this year, where some of the pieces were performed by professional actors. Owen describes the effect of reading it as “hilarious but uncomfortable; you squirm in your seat, asking yourself, could I be that one?”

Deliciously subversive and filled with bathos, almost everyone and everything is raked over the coals; from self-important academics to delusional community leaders; parodying the many idiocies of South African life. “He puts a pin into pomposity, ego and ignorance... deflates self-delusions, but does it lightly, with a smile” says Owen. He likened the seemingly pointless humour to Monty Python, Alan Bennet (Adding: “now that’s a compliment!”) and Ken Kesey’s One flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest .“Biting, cutting commentary, acerbic, merciless but above all, funny,” he concluded.

Krueger then read 'The Activist'. It is told from the rather warped perspective of the ‘leader’ of the Margate University Communist Society, who chastises fellow members for not forgoing their cell phones and continually updating their Facebook statuses.

It soon becomes a jumbled ride into the mind of a down-and-out, power hungry, washed-out student, who puts his foot into it by inadvertently revealing his own admiration for high status jobs and fat salaries, coupled with an (un)healthy penchant for Grand Theft Auto. Packed with gems such as: “Suggestions for lectures entitled ‘Revolutionising 24-hour clock time’ and ‘Why poor people have less money,’” Krueger had the audience guffawing with laughter, concluding the banal and absurd diatribe with the immensely ironic “...now that’s enough laissez-faire discussion for one meeting!”

by Anna-Karien Otto

20 September 2011

First published on the Rhodes University website.

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

Victoria Williams: 0127

Everyone could guess what was

happening. When they met at parties, he would first slap her face

then kiss her cheek.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)